- Home

- Savanna Welles

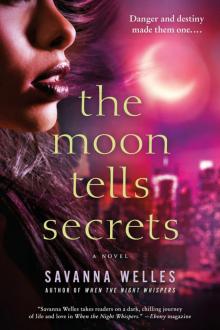

The Moon Tells Secrets

The Moon Tells Secrets Read online

Begin Reading

Table of Contents

About the Author

Copyright Page

Thank you for buying this

St. Martin’s Press ebook.

To receive special offers, bonus content,

and info on new releases and other great reads,

sign up for our newsletters.

Or visit us online at

us.macmillan.com/newslettersignup

For email updates on the author, click here.

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For Faith

acknowledgments

I’d like to thank my agent, Faith Hampton Childs, for her continuing support, encouragement, and most

of all, for her friendship. I’d also like to thank Monique Patterson for her editorial support and advice, as well

as Holly Blanck and Alexandra Sehulster for their editorial assistance. And to my family; my gratitude for always being there.

navajo skin-walker: the yee naaldlooshii

In some Native American legends, a skin-walker is a person with the supernatural ability to turn into any animal or person he or she desires.… Similar lore can be found in cultures throughout the world and is often referred to as shape-shifting by anthropologists.

Some have gained supernatural power by breaking a cultural taboo. In some versions, men or women who have attained the highest level of priesthood are called “pure evil,” when they commit the act of killing a member of their family, thus gaining the evil powers that are associated with their kind. It is also believed that they have the ability to steal the “skin” or body of a person.

There is a hesitancy to reveal these stories to those considered “others” or to talk of such frightening things at night.

—excerpted in part from Wikipedia

My subject is late. Our appointment was for nine A.M., but an hour has passed and I’ve heard nothing. A loss of nerve is often the case in matters such as this, particularly when one considers the consequence for betrayal of these “sacred” oaths. I hope the information offered will be worth my time and the fee I’ve offered to pay and that there will be no objection to my taping our interview.

I am eager—yet strangely wary.

—Denice Henry-Richards

Interview Notes

Recorded April 18, 2011, 10 A.M.

Subject: TKA

1

raine

There are days when I wonder why I was blessed with him—this boy I love with all my heart, who may cost me my soul. I know I must keep him safe from what wants him—wants us—dead, and that the older he gets, the more desperate it will become. Some nights I can’t close my eyes for worrying, can’t breathe, but then my son will kiss me on my cheek and whisper—Slow down, Mom, take a breath—and I’ll smile at him, and take that breath like he tells me to. Me, a full-grown woman, listening to an eleven-year-old kid.

I named him Davey for King David, who my granddaddy used to say was twice blessed by God. That was his name, too, and of all the family I knew, I loved him best. Before he died, he taught me how to read and draw and shoot a gun, an old pistol from the war he kept tucked away in his closet. I loved that name, David, the softness of it touched up with strength. But I didn’t know how blessed—or cursed—he was when I named him. That came later. His father, Elan, wanted me to name our baby after him, but we’d only been married a year before he died and Davey was born a month after he was gone. I was desperate then. I loved him so much, and I had a newborn son to raise and make as happy as I could—as blessed as I could make him. I couldn’t say Elan’s name out loud without weeping, and I didn’t want to cry those tears on my child.

I can say Elan’s name now but still wonder why he left us, even though that isn’t the whole truth and I know it. He didn’t leave, he was slaughtered, and I know the thing that took him is on its way for Davey, too, and me, because of what my son becomes.

You wouldn’t know it if you look at him. He was a pretty baby, is a good-looking boy, and will grow into a handsome teenager. Bright round eyes always on the edge of dreaming, and his Harry Potter glasses make them look bigger. Eyelashes so thick, the Foodtown lady teased him about them last week, that he must be using his mama’s mascara—unfair, she said, that a boy should have lashes as pretty as his. He just grinned, the tiny mole just on the side of his lip playing up his wide smile. His hair is black and iron-straight now; Navajo hair he got from his father and Grandmother Anna. He’s growing up fast, too fast, and within his boyish body I can see the contours of the man he will become.

His hair was kinky when he was little—curly-kinky like mine and soft around his face like an angel’s. My angel with skin as brown and smooth as a Hershey bar. I used to call him that: my Hershey bar with almonds—sweet with little bits of hardness poking through. That edginess will come out the older he gets, Anna warned, the fierceness, viciousness. I didn’t believe her, but I do now because I’ve begun to see it—unlike most of the stuff Anna told me. Usually I just smiled. Anna was as full of lies as she was of love, and half the time I didn’t believe what she said. But now I do, since she’s been gone; I know now she was telling as much truth as she dared.

She told me early about Davey shifting. Shifting ran through Elan’s family, she said, so I’d better get ready, and she’d smile her sly wolf smile, eyes as hard and cold as marbles. Elan must have had it in him, too, what Davey has, but he never showed it—not to me, anyway. It was in her cousin Doba, too, Anna said, who looked so much like her, people mistook them for sisters, but the resemblance ended at temperament. Anna hadn’t seen anyone in her family for years, not even Doba, whom she said she’d loved like a sister once. She never told me why she never saw her.

After Davey was born, I lived with my own people, distant family on my father’s side, until I got tired of them telling me I was nothing, that the damned baby made too much noise. They were set in their old, ugly ways, used to peace and quiet, and there was too much crying at night, they said, too much giggling in the morning. I moved out after that, to live with Anna, hidden like she was in her red brick house high on top of a hill, high enough so she could take in everything there was to see, be prepared for anyone who might be coming for us.

But the only thing that came for us was Anna, as far as I could tell. I was scared of her that first time I saw her shift and use the gift that Davey has. I decided then that there was nothing I could do but run from her, too, until she found us and brought us back, to keep us safe, she said. And I went because I knew then there was nowhere else I could go, not with Davey being like he was.

And then Anna died, leaving me alone to hide with the money she left, with those last words chasing me wherever I went: Don’t trust nobody. Not family. Not friend. Don’t let it get him like it got my son, not until he is ready to meet it. And remember that blood must pay for blood. A debt must be paid. Your boy can never forget. That is his destiny.

* * *

Davey tugged my arm, bringing me back to where we sat in this old church smelling of disinfectant, mold, and incense. The maroon velvet cushions in the pews were faded and ragged, and the pages of the hymn books stacked on rickety shelves so old and torn, they made me wonder how anyone could read them. Yet it was a graceful place—ceilings high and arched, streaks of light glimmering in through red and blue stained glass. No denomination. Probably started out one thing and ended up another. But it was sanctified, sacred space

; I could feel that.

“Hey, Raine? What we doing here?” he asked.

“Don’t call me Raine,” I snapped. I hated for him to call me Raine. It made me feel like he didn’t respect me, didn’t believe I was really his mother. I was so young when I’d had him, and Anna played mother for so long, taking over our lives, making the tough decisions, paying our way, it made me bitter.

“How come we’re here, Raine?” He was stubborn, like his mother.

“Cut it out,” I said. “I told you this morning, darlin’.” He didn’t like me calling him darlin’, any more than I liked him calling me Raine.

“Mom, please don’t call me darlin’! That’s embarrassing. That’s what you call a kid.”

“Then don’t call me Raine. How many times do I have to tell you that?” He gave me a half grin. A truce. I edged over to give a hug, and he eased away. Too old for that, too, especially in public. “We won’t be here much longer. I just need to go up front and pay my respects, say good-bye.”

“To who?”

“My aunt Geneva.” But it wasn’t just her; it was all of them—the ones I’d never heard from or known and just plain forgotten. My mother and father had died when I was a kid, and my grandparents died after Davey was born. As far as I knew, Geneva was the only family left from my mother’s side, and now she was gone, too.

“How come you need to say good-bye?”

“Because she’s my mother’s family.”

“Like Mama Anna.”

“Like Mama Anna. But from my side, not your daddy’s. Her name was Geneva Loving. Like my name was Raine Loving.”

“Didn’t Mama Anna have family, too?”

“Some.”

“What happened to them?”

“Dead, too, I guess,” I said, although I didn’t know.

I thought about Doba, remembering how I’d seen her at Anna’s funeral, she and the rest of Anna’s family. There’d been four there, all with that iron-straight hair and eyes that never left you. Anna’s uncle, whose name no one would say, sniffed around the house like he was smelling for something special until he left, and everybody looked relieved—even Doba, who followed his every move.

When Doba walked into the room, it was like Anna had sat straight up from her casket. Same iron-straight hair, worn brown face, thin fingers that stroked the air like they were tasting it. I’d wondered if Anna’s luminous eyes were hidden behind the dark glasses the funeral director gave us so the sun wouldn’t hurt our eyes. Doba must have cried as much as me. By then, I’d grown to love Anna like a mother, so I had a space in my heart for Doba, too.

She stared at me and Davey for a long time that day, taking us in like the long-lost relatives we were, made me promise to let her know where we were going so she could stay in touch. Don’t want to lose you like I did my cousin, she said. There aren’t that many of us left. Just him. She looked in the space where her father had stood, this uncle who had no name. I wondered if they all had the same “gift” as Davey, but I didn’t ask. I tried to stay in touch, but not so often as I should have.

“I miss Mama Anna,” Davey said.

I nodded and wondered if he saw her in his dreams like I did. Did she whisper warnings like she did sometimes in mine?

Davey suddenly tensed and pulled into himself, but not enough to be dangerous; he only did that when he was scared. Had something frightened him? I studied him closely, looking for the danger signs so we could get out quick. But there were none, just a kid in the loose-fitting Brooklyn Nets sweatshirt he got from Mack, my boss and the owner of Nell’s, the restaurant I managed. Davey used to say that Mack was his long-lost grandpa, and Mack would grin when he said it because he felt the same about Davey. Mack taught him to play poker, tie knots, make the chili he was famous for, like my granddaddy taught me stuff. Nell’s was the best job I ever had, the best place me and Davey had ever landed, until a week ago when I knew the thing had found us.

The dog came first, sniffing around Nell’s like it had business there, like it was looking for something to eat, slobbering at the mouth with those teeth pointed like they’d been filed, all white and sharp.

“Ain’t never seen no hound like that before, hellhound it look like,” Jimmy the counterman said when he came back from trying to chase the dog away; he was shivering even though the sun was out. My ears perked up. We’d been here nearly two years and hadn’t seen a hint. I’d started believing that Anna was wrong with all her warnings, that we’d finally have some peace from whatever she claimed was after us. Maybe it had just given up, gone away, left us alone. I pushed Jimmy for more. He’d given the hound some meat, he said, damn thing liked to snap his hand off, tried to run right through him, get its filthy self in Nell’s, Jimmy said, and I know Mack wouldn’t like that, would he, Rainey? A shiver slid down my back. But I told myself maybe it had just been “a hound,” like Jimmy called it.

Until it came back two days later.

Not every part of them makes it when they shift, Anna told me. That’s always the way with skin-walkers. Something doesn’t come back like it should, a nose looks like a snout, all wet and thick and nasty; an eye might be bigger than it should be and can’t be kept closed, claw tip fingers instead of nails, something will tell you, but you got to see it, Raine, Anna would say, and when you do, take that boy and run for all you’re worth. Don’t leave a clue behind you.

And that was what I’d always done.

It was in biker guise when it came back again. Must have gotten hold of some poor biker’s body and done God knew what with his soul. A red Harley was what it rode, heavy and loud, and the minute I heard it thundering down the road, I knew something was on its way. I watched it climb off the bike, keeping its thick body tight like it was guarding something that might bust out, face hidden by the visor on its helmet. Thick red gloves on its hands, walking on its tiptoes, cautious, like it hurt to move. It slid into a corner table, ordered coffee from Pam, our teenage waitress.

When the school bus dropped Davey off at Nell’s that day, it stared at him hard, like it knew him, and said something I couldn’t hear. Davey had just shrugged, given that funny halfhearted smile he always gave when he thought I worried too much, then joined me behind the counter. I warned him that night about talking to strangers, and he said he hadn’t talked, only nodded, just being polite like I tell him to be. I didn’t want to scare him, because I wasn’t sure. And it wouldn’t make its move right away. Anna had told me that it would play with us like a cat does its prey; it had to be sure the time was right, the night was right. Could be weeks before I saw it again.

But three days passed, and there it was, a dowdy old woman with white-streaked hair; full, pillowy breasts stuffed into a cheap flowered smock; eyes that stared from pink-tinted glasses as it ordered blueberry muffins; paws encased in delicate lacy gloves. I told Davey straightaway when I got home that night we had to go, and all he did was cry.

That didn’t surprise me. We’d traveled so much since Anna died, to this town and that, up and down the East Coast from Atlanta to Newark, even up to Boston, then back to Jersey. Wherever we went, he was always the new kid who couldn’t say where he’d been. Maybe kids teased him about that or sensed there was something “different” about him; he just never told me. Maybe that was why he cried so hard that night. I cried, too, knowing this was my fault for giving him this life, always running from something, scared to stay in one place long enough. Listening to Anna.

But despite our travels, Davey kept up with school however he could, and after a couple of months he always ended up near the top of his class. He was a reader, like my grandfather was, and he’d read anything you put in front of him—Harry Potter, Percy Jackson—maybe he identified with kids who had a wizard’s special edge. Comics he loved, too, and newspapers. Always did his homework—working till it was perfect. But in school he stayed to himself, shy of other kids, because they were shy around him. Yet this place was different. Maybe it was because of Mack helping him feel lik

e he belonged, maybe because we’d managed to stay so long. He’d felt safe enough here to make some friends. Hard-earned friends. Two years was a lifetime for a kid.

“So, Mom, where we going this time?” he said, voice cheerfully fake, his eyes focused on the Spy Mouse app on the Android cell I gave him last Christmas. A sharp pain etched itself into my heart.

“Baltimore.”

“Yuck!”

“How can you say that? You’ve never been there.”

“We’re not going to be able to take all the stuff we packed, are we? We’re going to have to leave most of it behind.” He turned off the game and glared at me, lips tight, all pretense of cheerfulness gone.

“We’ll take most of it with us.”

“Just most?”

“Yeah, most.”

“How?”

“We’ll rent a truck, okay?”

“Bullshit!”

“Don’t curse in church!”

“Don’t lie in church!”

“I don’t know how we’ll take it.” I met his glare with my own, and he looked away, unwilling to meet my eyes. “We’ll take the important stuff. All your stuff. Maybe we’ll rent a car. A van.” Mine would fit in a shoe box: photographs of Elan, of Davey as a baby, and of my grandfather David. Valentine cards Elan gave me before he died, birth certificates, mine and Davey’s. Davey’s stuff filled three of our four suitcases—books, DVDs, video games. Spider-Man toys from when he was three. But it was all important, even if it meant buying new clothes; his “stuff” was his anchor. It had taken him most of yesterday to pack it.

“Promise?”

“We’re in church, aren’t we?” He nodded. A truce.

The notice in the paper said the viewing would be from nine to ten thirty; we had been here since nine, but nothing was happening. A long oak table stood before an altar covered by rows of lit white candles of various heights. I hoped things would start soon because we needed to be on our way. After this was over, we’d grab something to eat, then get a cab and swing over to the apartment and pick up our things. I’d told the landlord I’d be gone for a couple of days. I didn’t give any notice, even though it meant losing my security. I didn’t want to risk him mentioning to anybody that we were gone for good.

The Moon Tells Secrets

The Moon Tells Secrets